On Fanny Howe: The Dragon of History

I’ll walk up to the canyons this weekend and I’ll watch the coyotes leaping into the brush, their easy lope, their backward shoulder gaze. Late at night, early morning, as they howl...

I never met Fanny Howe, who died on July 9, 2025. Poetry is anchored in community, and sometimes, when a poet dies, you feel like some thread of your poetic life has been unthreaded. You are missing a piece of the mystical literary world that carried you forward.

Poetry is a lonely business, and in that lonely world, we find our tribe. I like C.D. Wright, Anne Carson, Evie Shockley, Brenda Cardenas. The writers I find an alliance with are dirty-booted and wild. But we read beyond our own. Howe was a giant in the world of letters, someone poets like myself, who are just getting wet, would read and learn from. I want to re-read Fanny’s work, beginning with “Loneliness.”

I’ve struggled to understand how a famous person could feel lonely. I thought famous people were surrounded, and that it was the rest of us who got to enjoy loneliness. Fanny was well known her whole life, born into famous. In an interview with LitHub, Fanny recounts how she dropped out of Stanford and became a writer, a profession of the “family trade” that she felt would allow her to try to “live up to [her] privilege.

I found her experience of becoming a writer strangely opposite to my own life: the cult until age eighteen, the living in my car, then the attic, the struggle to get through state schools, then get a PhD, support a family, start a press with no money and no true reason. I stepped out of the cult and then made my already thrashed and beaten life as difficult as possible, as far from Martha’s Vineyard as one can be. Yet I enter Fanny Howe’s poetry and feel it beating inside me like a heart.

Reading Fanny’s poetry has always felt darkly familiar, even when I knew that I was out of step with every stage of her life. Her parents were famous writers. She taught at MIT. She lived on Martha’s Vineyard, a place I will never visit. As a poet, she was the sun.

But I kept on holding her idea up to the light—the notion of having something to live up to. Someone to impress.

What I love about her poetry is the well-travelled language that arrives in the present, in the moment, in a place we can all reach. Within her writing, Fanny is thinking about the world. She is paying attention. Not only to the physical details of living, but also to the way those details wind into our madness and ether.

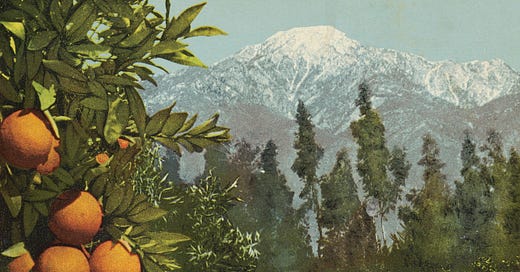

She writes of California, and desire, the coyotes, palm trees, Hollywood sign, “erotic canyons,” and a “quest for a perfect place,” and despite my largely opposite life, I feel all of it. The coyotes and wind and looming over us all; the concept of what we could have been—the lives we could have inhabited—had we been shiny, happy people.

I don’t know why her language and loneliness and the trill of her longing should feel familiar, and why, having never known her, I should feel sadness when she’s unthreaded from my life. But still, I feel her light gone out.

I live a blown life. Like many invisible writers who did not grow up with education or literary parents, and then spent too much time working (and, in my case, carrying other communities of writers), I’ve struggled to feel real as a writer. I didn’t have any writer friends until my forties. As I type these words, I can see the keyboard through my fingers. I may be a figment of my own imagination. Writing is lonely for those of us without.

But Fanny Howe wrote for all of us. She wrote profoundly of humanness. She was one of the great ones, and in her interviews and her writing, it’s apparent: her writing is an act of faith. She was solid, real; a stack of her own books sat on her shelves, a testament to a mind at work. And that poetry, branching from the mind, tended to the river of the soul.

Fanny is now at the river; she will be deeply missed. I will read her work again, and although I am unlikely to visit any of the places she wrote, I can live in her words. I’ll walk up to the canyons this weekend—the erotic canyons—and I’ll watch the coyotes leaping into the brush, their easy lope, their backward shoulder gaze. Late at night, early morning, as they howl across the canyons, warning the group of danger.

Fanny, we will miss you. We howl across canyons. Warning of danger. It is close.

You paid attention. You knew how history repeats itself.

Fanny, when I read your poetry, I will remember to keep writing, to keep walking ahead in pursuit of humanity and justice, to keep doing what I can to create a better world.

FROM THE DRAGON OF HISTORY

FANNY HOWE

I have seen it happen

A face with fangs and gills

represents history and an angel

is beating the beast on the back

Both are made of marble

One is a dragon

Its head is flat

like the iron tanks

in muddy water

that drove the men into the Gulf of Tonkin.

...

In my experience

the angel with his wings up

is trying to kill the dragon of history

to prove that air

is stronger than the objects in it

Thank you for this beautiful essay, Kate! 🌺

Thanks for your gorgeous and honest words, Kate.